by Nina

Namaste Berkeley recent informed us that even though it is only January our 2016 summer intensive is already sold out. At this point, they are just taking names for the wait list. Yes, we do realize that some of you will be disappointed at that news. Unfortunately the size of the room we’re teaching in means we need to limit the number of people attending.

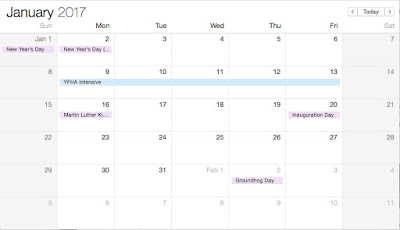

Because of this, we have decided to schedule a 2017 winter intensive at the same location. The dates will be January 9 through 13, 2017, with an extra day for teachers who want certification on January 14. This intensive will taught by Baxter and me, and will be exactly the same as the one offered for summer 2016 (see http://yogaforhealthyaging.blogspot.com/2016/01/sign-up-now-for-yoga-for-healthy-aging.html). So if you’re interested, save the date and stay tuned for registration information.

Both these intensives are organized by Namaste Berkeley not us, so I can’t reserve you a spot or even take names. But we promise to let you know as soon as Namaste opens registration for the Winter 2017 intensive.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

Friday Practical Pointers: Who Should Avoid Certain Wrist Movements?

by Baxter

We now arrive at one of our most delicate joints of the body, the wrist. I remind my students at least once a week that the human body has evolved to walk upright, freeing the wrists and hands from clomping around on all fours like our very distant ancestors. And yet, in modern yoga, we are down on hands and knees quite often, with poses such as Cat/Cow pose, Hunting Dog pose, and much more challenging poses for wrist integrity, strength, and flexibility such as Plank pose, Downward-Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) and Upward-Facing Dog (Urdva Mukha Svanasana) poses, and even Handstand! We are often asking a lot of our wrists, and for some it may be too much.

|

| Leslie Greinstein, Age 62 |

Movements of the Wrist

Start by taking your arms out in front of you with your palms turned up towards the sky—or imagine it.

Flexion: From the starting position, bending the palm of your hand toward your chest. We rarely use this movement in yoga asana, except in the version of Arms Overhead (Urdhva Hastasana) where you interlace your fingers, pulling the wrists away from one another, and take your arms overhead, with the backs of your hand facing the ceiling.

Flexion: From the starting position, bending the palm of your hand toward your chest. We rarely use this movement in yoga asana, except in the version of Arms Overhead (Urdhva Hastasana) where you interlace your fingers, pulling the wrists away from one another, and take your arms overhead, with the backs of your hand facing the ceiling.

Extension: From the starting position, dropping your hand forward and down so the palm faces away from you. We often use this movement in yoga asana, from the slight flexion of Downward-Facing Dog to the 90-degree flexion of Upward-Facing Dog, Plank pose, Side Plank pose (Vasithasana), and so on. Sometimes we bear our full weight with our wrists in this position, as in Handstand, and sometimes we bear just a light amount of weight on it, for example, in Extended Side Angle pose (Utthita Parsvakonasana) when the bottom hand is flat on the floor or block.

Abduction: From the starting position, moving the pinky sides of the hand away from the midline of your body. We use this movement when our hand is on the floor or a support to adjust the angle of our hand and wrist, such as in Downward-Facing Dog pose when we turn our hands toward each other or in Upward Plank pose (Purvottanasana) when we turn our hands out a bit.

Adduction: From the starting position, moving the pinky sides of the hands towards each other, toward the midline of your body. We use this movement when our hand is on the floor or a support to adjust the angle of our hand and wrist, such as in Downward-Facing Dog pose, when we turn our hands away from each other or in Upward Plank pose (Purvottanasana) when we turn our hands toward each other.

Note on Rotation: Although it feels like the wrist joints can rotate, this action actually comes from the forearm bones rolling over one another, not from wrist joint itself rotating.

Cautions for the Wrist Joint

Now let’s look at who should avoid or minimize certain wrist movements. Keep in mind, however, that we want to maintain as much of our full range of movement of the wrist joint as possible. So, in many instances, my caution will not mean “don’t” or “never,” but rather approach cautiously and stop if the movement worsens pain.

In general, most people can safely do all of the wrist movements if they are not bearing weight on the hands and wrists. In fact, a famous study published in JAMA in 1999 Yoga-Based Intervention for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome looked at using yoga to address one of the most common maladies of the wrist, carpal tunnel Syndrome, and all of the poses used where non-weight bearing poses. So even if you have wrist issues, you can still do a modified practice using lots of our poses!

In general, most people can safely do all of the wrist movements if they are not bearing weight on the hands and wrists. In fact, a famous study published in JAMA in 1999 Yoga-Based Intervention for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome looked at using yoga to address one of the most common maladies of the wrist, carpal tunnel Syndrome, and all of the poses used where non-weight bearing poses. So even if you have wrist issues, you can still do a modified practice using lots of our poses!

Generally avoid a particular wrist movement if:

Now for the specific movements. Who should avoid or minimize the following movements?

- The movement increases pain or numbness due to a painful wrist condition that is chronic, such as long standing repetitive strain injuries of the wrist, general arthritis or thumb joint arthritis, or more acute, such as acute sprains and strains of the wrist, carpal tunnel syndrome or new ganglion cysts.

- If you have significant swelling in the joint—whether from an acute injury or the flare of a chronic condition—and the swelling inhibits a particular movement or elicits significant pain during the movement.

Now for the specific movements. Who should avoid or minimize the following movements?

Flexion

- Those with carpal tunnel syndrome, which can worsen with flexion, even when non-weight bearing.

- Those with arthritis of the wrist that becomes more painful with flexion, especially when weight bearing.

- Those with a ganglion cyst (which usually appears on the back of the wrist).

- Those with hyper-flexible wrist joints may want to avoid full extension in weight-bearing poses to avoid wear and tear on the internal wrist structures and overstretching ligaments.

- Anyone who experiences significant numbness and tingling in the fingers and hands in extension while bearing weight in the wrist joints.

- Those with arthritis at the base of the thumb (the most common site for arthritis in the hand and wrist) or tendonitis of the thumb tendons, known as DeQuervain’s tendonitis, because abduction narrows the thumb side of the wrist joint which can compress the arthritic thumb joint or the inflamed tendon.

Adduction

- Those with arthritis the pinky finger side area of wrist because this action can narrow and compress this side of the wrist joint.

Techniques for Cultivating Flexibility with Yoga

by Nina

|

| De Jur, Age 57 |

After delving into strength (see Techniques for Strength Building with Yoga), Baxter and I immediately moved onto flexibility. Now, after our usual time spent on research, discussion, and debate, we’ve come up with a basic set of guidelines for how you can use your yoga practice for improving and maintaining flexibility.

An important thing to consider when you move into flexibility practices is how flexible you already are. Overly flexible people should emphasize strength and stability rather than promoting more flexibility. These people should do what they can do protect their joints by activating the muscles that support their joints (see below) and stretch less intensely than people who are naturally tight or even just average. Tighter people can safely move into a noticeable stretching sensation, as long as they are not feeling that sensation at tendon/bone connections near the joints.

How Far to Stretch. Be mindful in your stretching not to go beyond the sensation of a healthy stretch into feelings of pain, burning, or compression in your joint. If you experience sensations that seem unhealthy, either back off the stretch or use a prop or different variation of the pose. Overly flexible people should be extra careful, aiming for a lighter feeling of stretch (or even do the pose for strength instead flexibility by actively contracting their muscles instead of allowing them to stretch).

How Long to Stretch. To cultivate long-lasting flexibility in your muscles and fascia, aim for at least 90 seconds. If holding for 90 seconds isn’t possible, it might be an indication that you are: stretching your muscle too far or that the opposing muscles are contracting too tightly, that the initial intensity of your stretch set off a strong stretch reflex, or that you are doing a pose or a version of the pose that is too challenging for you. So start by seeing if you can back off the stretch a bit or modify the pose. But if you just can’t get comfortable, hold the pose until you are fatigued, and gradually over time work your way up to longer holds.

Static poses held for shorter periods of time will release the overnight tightness that we all experience and bring you temporary flexibility that will enhance the rest of your practice. For example, you could warm up for standing poses by doing leg stretches. Hold these warm-up stretches for 20 seconds or longer to trigger a relaxation in the muscles, allowing a more complete stretch.

How Often to Stretch. To cultivate lasting flexibility, stretch a particular muscle or muscle group regularly, at least three times a week and at most every other day. In general, with consistent practice, you can see results after 3 to 8 weeks for muscles. For fascia, however, it takes longer to create lasting changes, from 3 to 6 months.

Muscles need a day of rest between stretching sessions or you could develop an overuse injury. So generally you shouldn’t stretch the same muscle group on consecutive days. However, you can do flexibility poses every day if you focus on different areas of your body on each day, for example, alternating between upper body and lower body or between backbends and forward bends. Or, you can alternate intense stretching days with other types of yoga practice, whether that is active strength, balance, or agility practices, a gentle or restorative practice, or pranayama/meditative practice on your “off days.”

Static Poses. Entering into static poses slowly will allow elastic muscle lengthening to take place more easily. And, once in the pose, you can add in muscle activation on the opposite side of the joint to enhance the stretch (see below).

Dynamic Poses. Slow, dynamic movements in and out of poses allow gradual muscle lengthening without triggering the muscles’ protective stretch reflex. So these are a good way to warm up your joints in an easy fashion and can lead to immediate improvements in muscle flexibility, which you can then further with your static hold of the same pose. For example, you practice Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana) dynamically to temporarily improve hamstring/hip flexibility, which you then further with a long hold of the pose. In general, we recommend a combination of small dynamic sequences of stretches done for 6-8 repetitions, followed by holding the stretch statically for 90 seconds.

Restorative Poses. Poses where you can relax as you gently stretch your body in a supported position are an excellent way to cultivate flexibility. For example, holding Supported Backbend for at least 90 seconds allows you to gently open your front body. Likewise, holding Supported Child’s pose for at least 90 seconds allows you to gently stretch your back body. And because fascial planes run for long distances through your body, using a supported pose that stretches your entire body (front, side, or back) will help address fascial tightness as well as muscular tightness.

Balance Your Practice. To balance your flexibility, make sure your practice includes poses of all the basic types: standing poses, seated hip openers, backbends, forward bends, and twists, as long as they are safe for you. Of course you don’t need to do all these basic types within a single practice; just try to get to them sometime each week.

Activating Muscles. In static stretches, intentionally contracting the muscles on the opposite side of the joint—known as reciprocal inhibition—allows the muscle group you stretching to lengthen more effectively. So when you are stretching a particular muscle, bring your awareness to the antagonist muscle, which is the opposite muscle to the one you are stretching, and gently activate it. For example, when stretching your front thigh muscles in a Lunge pose, try consciously activating the back of your thigh. If you’re not used to working this way, it may take some practice. Take it in two steps:

- Consciously relax the muscle, allowing it to lengthen.

- Gently firm the muscle toward the bone.

Protecting Your Joints. For people with joint problems, such as arthritis, consciously firming the muscles that support a problem joint will help protect the joint from strain or wear and tear. For example, if you have knee arthritis and are practicing Reclined Leg Stretch (Supta Padangusthasana), you could firm around your knee joint as you bring your top leg into the pose and try to maintain that firmness as you stretch the back of your thigh.

For people who are overly flexible and can bend easily into deep forward bends and backbends, consciously activating the muscles that are supporting you in the pose will prevent you from hyperextending the joints. For example, in Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana), you can protect your hip joints by activating the muscles around your hip joints before you enter the pose and maintain as much of that as you can while you come into the pose. While the result will be a stretch that is not as deep as usual, your hip joints will benefit.

And just as over-stretching can cause joint problems in an active pose, it can also do so in restorative poses. So if you feel any sensations of overstretching, pain, pinching, or compression while you are in a restorative pose, come out and add more support, reducing the stretch you are experiencing. Likewise, if you notice pain in your joints after practicing restorative poses, add in more support the next time you practice.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

It's Complicated: Moving Toward Equanimity

by Beth

“It’s complicated.” That was our tour guide speaking from the front of the bus as it rumbled toward La Habana (Havana). She was describing the history, politics, and economics of Cuba. On day one of my 10-day cultural trip to Cuba with Global Arts/Media, I learned that in spite of certain guarantees from the Cuban government—free housing, education, health care and a monthly ration of food for each family—life is hard. Living in poverty is a daily reality for many Cubans, who supplement their meager salaries by selling whatever they can offer. Many simply beg and American tourists are the new target audience.

When approached by Cubans selling books, CDs, caricature sketches, or food, or simply asking directly for money, our guide informed us that the appropriate response for refusal was “No, gracias,” and that we could expect to repeat that phrase many times as once would not be enough for those who wanted our dollars or CUCs (special tourist pesos).

How true that turned out to be.

Dealing with the street vendors was easy. Because there was a concrete exchange involved, my answer always came after a few seconds of conscious thought. Dealing with begging was different. I’d seen examples of begging on television travel shows but I’d never experienced it up close and personal. Before leaving on this trip, I did what I do every December, sifting through the pile of solicitation letters from non-profit organizations and writing out checks to those that help feed, clothe, provide medical care for the poor and help children. But give money to people who walked up, looked me in the eye and asked for money directly with an open expectant hand? That was unnerving and I said, “No, gracias.” As an introvert, I felt really uncomfortable. And that feeling was later complicated by an emotional residue of guilt and “maybe I should have.”

Then two things happened.

I was standing outside Artesanos Cubanos, an artists’ collective, looking at my purchases, a necklace and a beautiful hand carved box with an OM symbol on the lid. I heard two sounds, a tapping and a clinking. When I looked up, I saw him. His blind eyes were filmed over and unblinking. The cane in his left hand tapped the cobblestones. His right hand shook a can with coins in it. He made his way carefully past me and continued down Obispo Street. Immediately, without a single conscious thought, I wove my way through the throng of tourists and locals to drop a handful of coins into his can. “Gracias,” he said.

“Por nada,” I replied.

The next day, again, spontaneously, without a conscious thought, I gave money to a one-legged man in a wheelchair who silently held out his hat as he sat by the fence at Plaza de Armas where our tour bus dropped us off.

Back home the phrase, “It’s complicated” filled most of my mind time. After thinking, mulling, and pondering for a couple of weeks I came up with three questions I wanted to answer in order to put my experience with begging in a context that would allow me to find some measure of peace with the emotional residue of guilt and “maybe I should have.”

1. Why was I so focused on this aspect of the trip as opposed to the artists and musicians I met and the culture I experienced?

This answer to this one was, thankfully, uncomplicated and twofold. First, I needed to understand the “why” behind my emotional response to direct begging. And, second, at this stage of life being free-tired,’ (I prefer the word “free-tired” to “retired”), I find myself blessed with time and a strong inclination to ponder how best to apply the tools of yoga to healthy aging.

,

2. What factors, conscious and unconscious, influenced my responses?

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras is my first go-to source for insight. I wasn’t sure where to begin, so I started from the beginning. My plan was to go one by one until I found what I was looking for. Turns out I didn’t have to go very far. I hit pay dirt at 1.7. I used The Unadorned Thread of Yoga (Salvatore Sambita) to survey 12 translations and then turned to the translation and commentary by I. K. Taimni, The Science of Yoga, which states:

(Facts of) right knowledge (are based on) direct cognition, inference or testimony.

My observation of the two men I gave money to offered direct cognition of their situation. One was clearly blind. If he had worn sunglasses, I might not have been able to deduce that fact. The other clearly had one leg. They did not directly ask for money so my “discomfort button” did not get pushed.

The other begging situations felt complicated. Although I had some general background on poverty in Cuba, I could not determine from observation or inference what their personal stories might have been, and since I did not speak the language, first-hand testimony was not possible. And as an introvert, I would not have asked.

3. Did I respond appropriately from a yogic perspective?

This one got really complicated for me. It took more thinking, pondering, and reflecting until I had my answer. In Sutra 1.33, I. K. Taimni states:

The mind becomes clarified by cultivating attitudes of friendliness, compassion, gladness and indifference respectively toward happiness, misery, virtue and vice.

The word "indifference" threw me. It can be so easily misconstrued as apathy or not caring, so I checked some of the other translations and chose the one by Georg Feuerstein:

The projection of friendliness, compassion, gladness and equanimity towards objects – [be they] joyful, sorrowful, meritorious or demeritorious – [bring about] the pacification of consciousness.

The word "equanimity" felt right. It means mental or emotional stability or composure, especially under tension or strain.

My experience with the blind man and the man with one leg was peaceful. My response was immediate—there was no emotional charge, positive or negative. Equanimity was present. Even though I felt compassion toward those who asked directly for money, I did not experience equanimity, as my discomfort and the emotional residue of guilt and “maybe I should have” clearly demonstrated. I reacted instead of responding. If equanimity had been present, no matter my choice of action, there would not have been that strong emotional charge.

This was the Aha! moment that uncomplicated my confusion and discomfort, and raised two more questions. How does one respond to both perceived joy and suffering with equanimity? Is it possible to experience life’s ups and downs in this five-senses material world without emotional charges, positive or negative?

The answers, for me and for many of us, are both complicated and uncomplicated. It can feel complicated when we first confront and grapple with the concept of equanimity. It’s less complicated if we practice svadhyaya (self-study) and reach a point of understanding. It slowly becomes uncomplicated when that understanding filters through body, breath, and mind as we practice equanimity using the wisdom and tools of yoga.

So, it looks like I have my work cut out for me. It’s been six weeks of thinking, mulling, and contemplation. With this new awareness I can begin practicing. I am sure that it will be a long slog. I will, no doubt, take one step forward and two steps back, and then repeat the process over and over again. The concept of equanimity is now “top of mind,” and will be a new aspect of my yoga practice, from asana to meditation.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

Flexibility Varies: Are You Tight or Flexible?

by Baxter

As you can see from these photos, anyone observing Nina and me practice Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana) would immediately see that even though we’re both long-time practitioners, our ability to stretch the muscles in the backs of our legs varies greatly. Yes, it turns out that flexibility among people varies, and often quite a bit! Some people are naturally tight, some are naturally flexible, and others are overly flexible.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

As you can see from these photos, anyone observing Nina and me practice Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana) would immediately see that even though we’re both long-time practitioners, our ability to stretch the muscles in the backs of our legs varies greatly. Yes, it turns out that flexibility among people varies, and often quite a bit! Some people are naturally tight, some are naturally flexible, and others are overly flexible.

There are three factors that influence our flexibility:

- Joint stabilizing structures of the joint capsule and ligaments might have more or less flexibility. (You might detect this by sensing limitation or restrictions near to your joints.)

- Muscle length or fascial tightness. (You might detect this by sensing the limitation or restriction mid-muscle or along the length of a muscle group.)

- Disease processes that affect flexibility, like generalized arthritis or Parkinson’s disease, which can gradually decrease flexibility over the long haul. Certain rare conditions can have more extreme effects on flexibility, such as Ehler-Danlos Syndrome, which makes people hyper-mobile and scleroderma, which makes people severely restricted.

When you practice for flexibility, you should take all of these factors into consideration. If you’re naturally tight or have average flexibility, we recommend you begin with dynamic poses to warm up and release your overnight tightness, and then practice static stretches that you hold for least 90 seconds, if possible, to increase your chances of increasing your resting muscle length and improving your range of motion.

If you are overly flexible, attempting to become more flexible may actually be dangerous, as you risk of worsening the lax support your joints already have. So even though being more flexible would enable to do super bendy poses with greater ease, we recommend that you focus on strength instead. Include more strengthening poses in your practice, and use isometric contractions around your joints in all your poses (see Why and How to Activate Your Muscles in Yoga Poses), including your stretching poses.

Although there is no official standard for “average flexibility” means, you can assess yourself by doing the following basic poses and comparing your range of motion and flexibility with those of fellow practitioners, or have your teacher watch you do them and ask for their feedback assessment:

- Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana)

- Crescent Moon pose

- Triangle pose (Trikonasana)

- Lunge pose (Vanarasana)

- Bridge pose (Setubanda Sarvangasana)

- Cobbler's pose (Baddha Konasana)

- Easy Sitting Twist (Parsva Sukasana)

Once you have identified your tight areas, you might want to focus more attention on increasing flexibility those areas. For instance, due to being flexible in the hip muscles that allow me externally rotate my legs, poses such as Cobbler’s pose (Baddha Konasana) and even Lotus pose are fairly easy for me. However, as you can see from the photo above, my hip muscles that allow forward bending (flexion), which is required for Standing Forward Bend are much more restricted. So, it behooves me to spend more time on lengthening the muscles that inhibit forward bending from my hips, rather than focusing on hip stretches for Lotus-like poses that I don’t need more flexibility to achieve.

So, when thinking about how you can influence your own flexibility, be sure to take a good look at your body as well as your health history. This will enable you to design a customized practice that will benefit you as an individual and help keep you safe.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

Video of the Week: Arms Overhead Vinyasa

This is a simple but powerful vinyasa that you can use on its own to energize yourself or uplift yourself, or include as the first or even the last pose in a yoga practice.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

Friday Practical Pointers: Who Should Avoid Certain Knee Movements?

by Baxter

Our tour through the body’s major joints continues today with a look at who should avoid certain knee movements. When it comes to possible movements, the knee joint is a quite a bit simpler than the hip and the shoulder as it is mostly about bending and straightening. But because of its role in standing, walking, and running, the knee is one of the most commonly injured joints and very frequently affected by the wear and tear of osteoarthritis.

|

| Flexion and Eternal Rotation by Melina Meza |

Movements of the Knee Joint

Flexion: Bending your knee (moving the lower leg bones backwards toward the upper leg). You make this movement when you move into bent-knee standing poses such as Warrior 1, 2 and Side Angle Pose when the front leg goes from straight to bending the knee over the ankle. The movement is also essential for bending your knee more deeply, such as when sitting in Hero pose (Virasana) or Child’s pose (Balasana).

Extension: Starting from a bent knee position, straightening your knee (moving the lower leg bone forward and away from the upper leg). The opposite movement of flexion is extension, so anytime your knee is bent and moves towards straightening, your knee is going into extension. You make this movement when you exit from Warrior I or 2 (Virabradrasana 1 or 2) or Extended Side Angle pose (Utthita Parsvokanasana) or in the transition from Warrior 1 to Warrior 3. You also make this movement when you lift your back leg in Hunting Dog pose, come into Cobra pose (Bujangasana) from Child’s pose (Balasana), or move into Downward-Facing Dog pose (Adho Mukha Svanasana) from all fours.

Internal Rotation: When your knee is bent, rolling the lower leg bones in, towards the midline of your body. The lower leg can internally rotate a small amount at the knee joint only when the knee is in flexion. You make this movement in Hero pose (Virasana), both seated and reclined versions, as well as in the many seated poses that have one leg in Hero pose.

External Rotation: When your knee is bent, rolling the lower leg bones outward, away from the midline. The lower leg can externally rotate a small amount at the knee joint when the knee is in flexion. You make this movement in many bent-knee seated and reclined poses, including simple ones like Cobbler’s pose (Baddha Konasana), both seated and reclined, more complex ones like Half and Full Lotus poses (Padmasana).

Note: When the knee joint is in full extension, such as in Mountain pose (Tadasana), your lower leg cannot independently rotate from the knee, either internally or externally. In this case, when your upper leg rotates from the hip, your lower leg goes along for the ride. You can see this when you turn your front leg out to prepare for pose a standing pose like Triangle pose (Trikonasana) or in a straight leg seated pose, such Wide-Angle Seated Forward Bend (Upavista Konasana).

Cautions for the Knee Joint

Now let’s look at who should avoid or minimize certain knee movements. Keep in mind, however, that we want to maintain as much of our full range of movement of the knee joint as possible. So, in many instances, my caution will not mean “don’t” or “never,” but rather approach cautiously and stop if the movement worsens pain. In general, you should avoid or minimize any knee movement if you have:

- Acute painful injury to the knee area that gets worse with that movement, whether from a sports activity, such as acute ligament sprains, or a problem like acute bursitis that is the result of bumping your knee cap or over use.

- Chronic issues that flare with that movement, such as those with knee joint arthritis or those with meniscal and ACL ligament injuries that have not been repaired or even, in some cases, that have been surgically repaired.

Flexion

- Those with significant swelling in the joint, whether from an acute injury or the flare of a chronic condition, such that the swelling actually inhibits movement or elicits significant pain when movement takes place.

- Those with Patellar Femoral Syndrome, a fairly common condition affecting the knee cap and knee joint, which often is worse with flexion.

- Those with arthritis of the knee that become more painful with flexion.

- Those with bursitis at the kneecap area or with a Baker’s cyst at the back of the knee.

- Those with ACL repairs who need to avoid extreme flexion, such is in full Child’s pose (Balasana).

Extension

- Those with tears to the ACL ligament need to avoid sudden strong extension, such as stepping from Lunge pose (Vanarasana) to Downward-Facing Dog pose (Adho Mukha Svanasana), or jumping from Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana) to Downward-Facing Dog pose.

- Those with hyperflexible knees may want to avoid full extension in straight leg poses to avoid wear and tear on the internal knee structures and ligament over-stretching.

- Those who experience increase pain in the knee in poses where the knee is both flexed and internally rotating, such as Hero pose (Virasana), both seated and reclined, and the seated twists where one leg is in Half Hero pose (Adra Virasana).

- Those with tears to the meniscus (the half moon cushion of the knee) where increased pain or locking of the knee occurs with flexion and internal rotation.

External Rotation

- Those who experience pain in the knees where the knee is both flexed and externally rotating, such as Cobbler’s pose (Baddha Konasana), both seated and reclined, Half and Full Lotus poses (Padmasana).

- Those with tears to the meniscus (the half moon cushion of the knee) where increased pain or locking of the knee occurs with flexion and external rotation.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

After Hurricane Katrina

by Mary Ann Avallone-O’Gorman

|

| Natural Disaster by Leonardo da Vinci |

Yoga Sutra 1.1 “Now, after having done prior preparation through life and other practices, the study and practice of Yoga begins.” —translation from Jnaneshvara

February 2016 marks my ten-year anniversary of studying and practicing yoga. I first came to the mat after Hurricane Katrina.

I live in Katrina-land, on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, in the shadow of New Orleans, and after the storm, I was ankle deep in mud and devastation. A piece of my porch railing served as a horizontal ladder in my front hall, thrown there by the storm surge that roiled through my house overturning refrigerator and piano, and floating a table loaded with pottery twenty feet down a hall, around a corner, and finally coming rest on top of a fallen mantle with pottery still intact. My life was bayou sludge, dead animals, rotten food, destroyed photographs. I spent months preparing my gutted house for rebuilding and also making the now four-hour drive into New Orleans (90 minutes before Katrina) to work on my destroyed rental property there, where, alone on the desolate city street, I warded off the rumor of armed vandals with the talisman of my large pickup loaded with a generator and shovels.

My marriage had been crumbling before Katrina, and the weaknesses of that structure grew, as if the storm surge had poured its polluted waters into all the fracture lines.

For months my life was hard physical labor. I was forty-seven and in good shape, but my body wasn’t made for lifting wet mattresses, pushing wheel barrows of soaked drywall, or single-handedly pulling down a tilting carport rotted out by the water. I was pretending I had super powers, which included functioning without self-care. I had a makeshift kitchen where I could cook healthy meals, but mostly I lived on rotisserie chicken, take-out, and wine. Lots of wine to help me sleep in the shell of the house within the shell of a marriage.

One afternoon six months after the storm, I drove by the local yoga studio and noticed it was open, so I stopped in. I don’t know why. I’ve always been, and still am, skeptical about any organization of any kind. But I went in and the owner, Eileen, was at the desk. I immediately put up as many walls as I could and looked to see how she was ‘other” from me: tattooed, smiling, warm, friendly. I was none of these. We talked a little, and she noticed my black lab had taken over the driver seat of my car. We shared a good laugh about the large dog in the front seat of my Honda Civic. So I decided to try yoga basics and went back that night.

My whole life I had been an active person. I’ve been a distance swimmer, a weight lifter, and a long walker. I gave up running in my late twenties when my knees just said no, but I took up aerobics when it was the trend. I felt I had a grip on my body.

I had a grip on my body.

My first yoga class was gentle yoga basics. Our first practice was three-part or dirgha breath. I could not breathe. As the class progressed, the grip I had on my body became more evident. No muscle cooperated, and I blamed the instructor and the ridiculousness of yoga.

As sutra 1.1, says, “through life and other practices” I had prepared myself for yoga. I had trained myself to resist anything my body thought was intelligent. I clung to a completed marriage, I carried glass shower doors over my head for the length of a city block, I loaded a generator and dehumidifiers and thirty pounds of extension cords in a pick-up before sunrise and drove 100 miles to unload it all and spray chemicals on exposed studs to prevent mold. I would not wear a mask. I drank wine for dinner and ate sugar for breakfast. I began the study and practice of yoga with a set of experiences that prepared me for that first class in ways that no one could predict.

I sighed and eye-rolled through the most basic of poses, thinking all along this class was a mistake. Then Eileen instructed us through Savasana. The studio had no windows and as I reclined on my mat, I felt safe for the first time in months. My home’s second story was intact and I lived there, but my first floor—on good days a dramatic space full of water views on three sides—was a windblown, door-less, windowless, wall-less space. The dogs delighted in walking through the studs, but I felt exposed to the elements, the hurricanes that came after Katrina, the cold northeast winter winds, the surviving raccoons, possums, snakes. Here on my mat in Savasana, I was cocooned. Eileen talked us through the pose, and I soon felt the breathlessness that precedes sobbing.

Then I was sobbing. In February 2006, for the first time since August 29, 2005, I was crying. I had smothered the sobs with heavy lifting, heavy drinking, crazy eating, crazy hours, anger, and more anger. And now the sobs could not stop. I tried to stifle them, and left quickly after class. In my car, I sobbed more and had trouble driving the few miles home, staying in second gear because I could not cry and shift. For once, feeling took precedence.

I walked through the dark wind tunnel of the first floor of the house and went upstairs to my bedroom where my then-husband was reading the New York Times on the computer. I sat on the floor and leaned against the bedframe and sobbed until I was retching. He sat in the light of the computer screen and said, “Maybe yoga isn’t for you.”

That’s when I knew so many things, the most important being that yoga was for me. The prior preparation I had done “through life and other practices” had led me to the mat, despite my skepticism. My successful attempts at strong-arming through all adversity—through natural disasters and relationship disasters—painted me into a corner. The only way out was to soften into ease and grace.

As I come up on my ten-year anniversary, I come to my practice every day with new preparation, new practices. I say to my students, “You bring your whole life to the mat. Your wisdom. Your strength. Your failures. Your attitude about all these things. Use what serves you. Observe what does not. Place it gently to the side. That act, in itself, is a yogic practice. Recognize all the traits you bring to all that you do. Allow your yoga practice to be exactly that: a practice of and for your whole life.” But I am talking to myself. Happy anniversary to me, and to all yoga practitioners who come to the mat for a day, week, year, a lifetime.

Namaste.

Mary Ann Avallone-O’Gorman (E-RYT, MA, MFA) now lives in a home out of the flood zone with a new black lab and various cats. She owns and is the sole teacher at Studio 2.46 (Practice with Strength and Grace) in her yard as well as at the wonderful River Rock Yoga in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, and at two domestic violence shelters on the Gulf Coast. She practices and studies Ayurveda, and writes her heart out on a regular basis. Her chapbook of poetry Life in This House is available through Amazon.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect

Langganan:

Komentar (Atom)